Few phrases in popular culture carry as much spooky weight as “the curse of the pharaohs.” It conjures images of dusty tombs, glowing hieroglyphics, and shadowy figures dropping dead the moment a sarcophagus is cracked open. At the heart of this legend lies the story of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, discovered in 1922 in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. The claim: anyone who dared disturb the boy king’s resting place would be struck down by a supernatural curse.

It sounds like something straight out of a horror movie. In fact, it pretty much became a horror movie — or at least fueled a century of books, plays, films, and sensational headlines. But how much of this was real, and how much was the product of tabloid journalism, overactive imaginations, and perhaps a few well-timed cases of bad luck?

The Discovery That Shook the World

In November 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter and his team, backed by wealthy patron Lord Carnarvon, uncovered the sealed tomb of Tutankhamun. Unlike most other royal tombs that had been looted centuries earlier, this one was remarkably intact. Inside lay golden treasures, ritual objects, and the famous golden death mask that has since become an icon of ancient Egypt.

The discovery was the archaeological equivalent of finding the Holy Grail. Newspapers worldwide printed daily updates, and the “boy king” captured the imagination of a global public. But then, just months later, things took a darker turn.

The Death That Sparked a Legend

In April 1923, Lord Carnarvon, the financier of the expedition, suddenly died in Cairo. His cause of death was septicemia — blood poisoning that resulted from an infected mosquito bite. Not exactly a mystical lightning bolt from Ra, but dramatic enough to set off alarm bells in the press.

Within days, London newspapers began running with the story: Carnarvon had been struck down by “The Curse of the Pharaohs.” Reporters claimed that a curse had been found inscribed in the tomb warning of death to all who entered. While no such inscription was ever discovered, the legend snowballed overnight.

Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes and enthusiastic spiritualist, even chimed in, suggesting Carnarvon’s death was caused by “elementals” (spirit guardians of the tomb). That was all the tabloids needed. The story of the curse spread like wildfire, proving once again that nothing sells papers like a good ghost story.

The “Victims” of the Curse

Carnarvon’s death was just the beginning of the curse narrative. Over the next decade, every illness, accident, or untimely passing connected to the expedition was chalked up to Tutankhamun’s wrath. Some examples:

- George Jay Gould, an American railroad magnate who visited the tomb, died of pneumonia in 1923.

- Aubrey Herbert, Carnarvon’s half-brother, died in 1923 from blood poisoning following a dental procedure.

- Arthur Mace, a member of Carter’s team, died in 1928 of suspected arsenic poisoning (though tuberculosis was more likely).

- Howard Carter’s canary was allegedly eaten by a cobra — Egypt’s royal symbol — on the day the tomb was opened.

All of this fed the narrative that Tut’s curse was alive and well. Newspapers loved it. Hollywood loved it. The public, primed by the Gothic and supernatural obsessions of the early 20th century, ate it up.

The Skeptical Reality

Of course, skeptics and scientists point out a few glaring problems with the curse theory.

1. Survivorship Bias:

Out of the 58 people directly involved in opening the tomb, only about 8 died within the first decade. The majority, including Howard Carter himself, lived long and healthy lives. Carter, in fact, died in 1939 at the age of 64 — 16 years after the tomb was opened — with no mysterious curse in sight.

2. Medical Explanations:

Carnarvon’s death was not unusual for the time. Infections from minor cuts and insect bites were often fatal before the widespread use of antibiotics. Pneumonia, blood poisoning, and tuberculosis were also common killers in the 1920s.

3. No Actual Curse:

Despite popular belief, there was no inscription inside Tutankhamun’s tomb warning of death. That detail appears to have been pure invention by journalists eager to spice up their coverage.

4. Mold and Bacteria Theories:

Some modern researchers have suggested that mold spores or bacteria present in the sealed tomb could have contributed to illnesses. While it’s possible that ancient tombs contained dangerous pathogens, there’s no evidence they played a significant role in Carnarvon’s death or anyone else’s.

Why the Curse Endures

If the “curse” wasn’t real, why does it remain so powerful in popular culture? The answer lies in psychology and storytelling.

Humans love patterns. We’re wired to link unusual events together, even when they’re unrelated. A string of deaths tied to a tomb discovery feels more meaningful (and more entertaining) if you wrap it up in the cloak of an ancient curse. It’s also a great way for newspapers to boost circulation and filmmakers to sell tickets.

The curse of King Tut has inspired countless horror films, from Universal’s The Mummy (1932) to Brendan Fraser’s adventure blockbusters in the 1990s. It has also become a shorthand for the dangers of messing with things “man was not meant to disturb” — a theme that echoes in everything from Indiana Jones to modern conspiracy theories.

What It Means Today

Today, the curse of King Tut is less about ancient Egypt and more about modern media. It’s a case study in how myths are manufactured, spread, and kept alive long after their factual basis has crumbled. The story shows us the power of coincidence, the allure of mystery, and the way superstition can piggyback on real events.

Tutankhamun himself, who died at around 18 or 19 and left behind a short, troubled reign, probably never imagined he’d be remembered more for a “curse” than his actual life. Yet here we are, a century later, still talking about him.

If there’s a real curse here, it’s the curse of publicity: once a story catches the public imagination, it never dies.

Final Word

So was there a curse of King Tut’s tomb? Not really. Unless you count mosquito bites, bad dental work, and the hazards of early 20th-century medicine. But as legends go, it’s one of the best — a perfect storm of mystery, coincidence, and cultural fascination that continues to remind us that humans, more than mummies, are the real myth-makers.

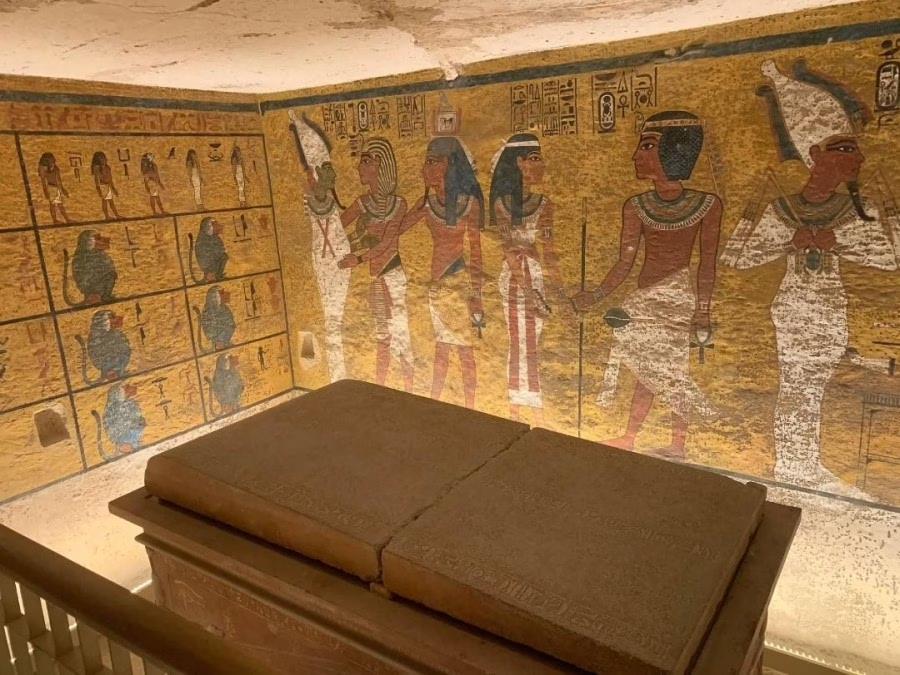

And to make it that much cooler…here are some family photos visiting King Tut’s Tomb back in 2020.